Bogeyman

This long blog is based on a Zoom presentation I gave on B.C.’s GovInfo Day, May 6, 2022, for librarians and library staff, sponsored by Simon Fraser University and others.

Fees are the bogeyman of freedom of information.

Requestors are quick to condemn them as barriers to transparency.

Government officials often wring their hands about the high costs of FOI to the public purse.

While there’s some truth to both positions, there’s also a lot of dishonesty.

As a journalist with almost 40 years’ experience using FOI, I think it’s time for an adult conversation about fees.

The conversation is especially needed now that British Columbia has for the first time imposed an FOI application fee, $10, which is a setback for requestors. Meanwhile, Ottawa has eliminated all processing fees for Access to Information Act requests – a measure that paradoxically is also a setback for requestors. I’ll explain that in a moment.

Fees in British Columbia were never an issue for requestors until last fall, when the new application fee was levied with virtually no consultation.

Provincial summary statistics for 2018-19, the last year posted, show that only 151 requests out of 7,222 attracted any fees, and the average charge for those few was just $5. The British Columbia FOI regime has historically been very inexpensive for the ordinary user.

The province commissioned management consultant Deloitte Canada to examine the cost to the public treasury of processing all those requests. Deloitte’s 2019 report came up with an astonishingly high number: an average of $3,000 for each request. (The average processing cost per request at the federal level is about a third of that, though the accounting methodologies are not directly comparable.)

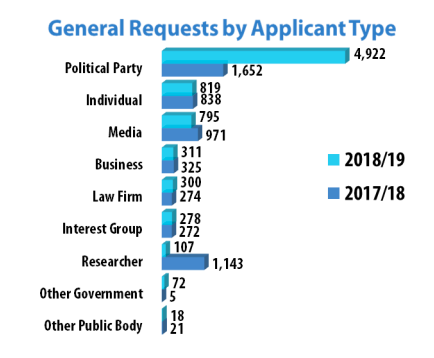

At the same time, there was a sharp spike in the number of new requests coming through the door, all of them from opposition parties. The 2018-19 statistics show that almost every other category of requestor, including media, reduced their numbers while political parties tripled theirs.

Justifying the new application fees, Lisa Beare, the citizens services minister, noted that the B.C. Liberal opposition had made 4,772 requests in 2020-21. She multiplied that number by Deloitte’s $3,000 for each request, and came up with a total of $14.3 million to service the opposition.

Here the crass politics of fees were laid bare: journalists and other requestors had changed little about their use of the law. But two political parties now were duking it out in the FOI arena. And all users got sideswiped by the government’s dishonest claim about the hemorrhaging of public dollars because of an implied abuse of the FOI system. This is what I call a bogeyman.

The Deloitte study about the so-called exorbitant cost of FOI has also been mischaracterized, spun for political purposes.

Drill down into the details, and you quickly learn that much of the high cost of administering FOI in the province derives from poor records management, inadequate IT systems, awkward workflow and a failure to implement basic artificial-intelligence solutions that now are standard in other organizations, such as private law firms. In short, the province is grossly inefficient in information processing.

Slapping an application fee on new requests was therefore an ass-backwards approach to controlling costs. A government genuinely intent on fixing the problem would streamline its back office, not perpetuate inefficiencies by reducing demand at the front end through fee barriers. But conjuring bogeymen is of course easier, and scores political points.

To be clear, though, I am not against fees in FOI regimes. In my view, a properly structured charging scheme actually benefits users. To explain, we need to look at the federal access-to-information system.

Fees have never been a barrier for users of the federal system. Ottawa historically collected very little money from fees, usually amounting to less than one per cent of total processing costs. For example, in 2015-16, the average charge to users, on top of the standard $5 application fee, was just 56 cents per request. The information commissioner has received very few complaints about fees.

In the 2015 election campaign, the Liberal party under Justin Trudeau presented itself as an alternative to the Conservatives under Stephen Harper. Harper’s government had enacted many transparency measures, including a few needed improvements to the Access to Information Act. But in its later years, it acquired a reputation for secrecy, such as fewer and more restricted interactions with journalists, for example.

So Trudeau made a grand transparency promise – to eliminate all fees for access-to-information requests, apart from the initial $5 application fee. His government delivered that promise in May 2016, and since then no one has been charged for searching, processing, reproduction or anything else. (Never mind that fees were never an issue for users.) And fee elimination was later embedded in the law.

On the face of it, doing away with fees is heaven for requestors.

The reality is more like hell.

The new free-for-all policy has removed discipline from the access-to-information process. Requestors now have a much-diminished incentive to narrow the scope of their requests, and departments have little choice but to accept them, however sprawling they may be. (There is now provision to reject a request that “is vexatious, is made in bad faith or is otherwise an abuse of the right to make a request for access to records.” But this provision has turned out to be difficult to invoke and is seldom used.)

The result? We have inaugurated an era of monster requests.

At Library and Archives Canada, there have been at least two requests for the RCMP’s Project Anecdote file, a fraud investigation closed long ago with no charges ever laid. The 780,000-page archived file will require at least 26 people working for six years to vet, at an estimated cost to the treasury of more than $21 million. As you might imagine, Library and Archives is resisting.

In 2017-18, the Canada Border Services Agency processed 14.8 million records for a single request, collecting only the $5 application fee to cover costs. Another federal institution processed almost 15 million records in 2019-20 in response to just three related requests, for a total fee of $15.

These examples are extreme, but there are many more large, complex requests that now are overwhelming understaffed ATIP units. The inevitable result has been growing delays in responding to requests, and growing backlogs of unprocessed requests carried over into future years.

The impact of COVID-19 has certainly contributed to the delay problem, and even masked it to some extent. But as the pandemic recedes, we will see with ever more clarity how the elimination of fees has triggered a user stampede for departmental resources. And responsible users, who keep the scope narrow and focused, will be losers, stuck behind monster requests that suck up all the manpower.

And so a fee-free regime has an insidious hidden cost: less timely access to government records. What may once have been a response time of weeks or months will now be measured in years. In my profession of journalism, that’s a story killer. We might as well all become historians.

Ask yourself who really benefits from such a gummed-up regime. Certainly not users, stuck more often with stale, outdated documents of little value to public discourse. Governments, though, will certainly benefit from dodging document-based accountability long enough for the issues to fade from public memory.

So fees can work to government advantage either way.

In B.C.’s case, application fees will almost certainly reduce the number of FOI requests coming through the door. There is hard empirical data showing exactly that result when Ontario raised its application fee in the 1990s and Nova Scotia did the same in the early 2000s.

And Ottawa’s recent elimination of processing fees has attracted more requests, at an enormous cost in delays, but effectively sparing government from timely scrutiny.

So what does a rational fee regime look like, one that doesn’t play political games?

On one point, there is universal agreement. In every country and jurisdiction with a freedom-of-information law on the books, fees never come even close to recouping the costs of administering FOI.

To use British Columbia as an example, fees recover only about two-tenths of one per cent of the indirect and direct costs (based on the Deloitte study). That low level is typical of every FOI regime, including at the federal level.

Rather, fees are designed to ensure requestors are focused and reasonable, and do not lay automatic claim to inordinate amounts of public resources. Typically, fee schedules provide a certain amount of no-cost or low-cost service, then escalate for larger, more complex requests.

Now some requestors balk at any fees, arguing the public has already paid for the information, that the information is in fact owned by members of the public. But no FOI system ever charges for information per se. Rather, fees cover some of the costs of locating, gathering, collating, reviewing, processing, vetting, and copying information – much of the work labour intensive, and much of it customized to the needs of a single citizen.

In my view, the fairest approach to user fees is to make applications free of charge, and to include several hours of no-charge processing, say five hours. (In B.C., it’s three hours currently.) This approach should cover the majority of requests. Note that there is no charge to file FOI requests in many countries, including Britain, Sweden, Ireland, and the United States.

At the federal level, the application fee of $5 was set in 1983 and has never changed. Had it kept up with inflation, the fee would now be $12.97, so requests have been getting cheaper to file. Meanwhile, the cost of cashing a $5 paper cheque is now about $50. Even an online payment costs 40 cents to process. So this gatekeeping-by-fee has become absurd and pointless. Ottawa needs to ditch the fee.

In a rational fee regime, larger and more complex requests should incur progressively higher fees, based on a rate card keyed directly to hours. For example, an additional 10 hours (beyond the free hours) might be charged back at $15 hour, or the minimum wage. Any such system must have clear rules and be premised on reasonably efficient back-office processes in government. There should also be a fee-waiver option, based on a clear set of principles and adjudicated by a neutral party.

But whatever fee structure is considered, it’s important not to be distracted by bogeymen. By spurious claims that users are abusing the system. By the fuzzy notion that information should be free. By political game-playing. Fees serve a useful public purpose but must be designed to serve the public good, rather than as a tool to stifle scrutiny.

May 6, 2022

UPDATE: The British Columbia government in June 2022 published a new annual report on FOI, covering 2019-20 and 2020-21, which shows a general decline in the number of new requests, including from political parties. The statistics undermine the claim that rising numbers were a drain on the provincial treasury.

July 4, 2022