Carping about complaints

Like most freedom-of-information regimes, Canada’s federal law allows unhappy requestors to lodge formal complaints. But what happens when you want to complain about the complaints process? You write a blog!

Canada’s law has some positives for citizens dissatisfied about the processing of their requests under the Access to Information Act. For one, registering a complaint with the information commissioner of Canada is free. In other jurisdictions, such as Ontario, an appeal to the ombudsperson costs as much as $25. And for requests made after June 2019, Canada’s information commission can order institutions to release information. Before that date, she could only encourage them to do so or, in a few instances, take them to court.

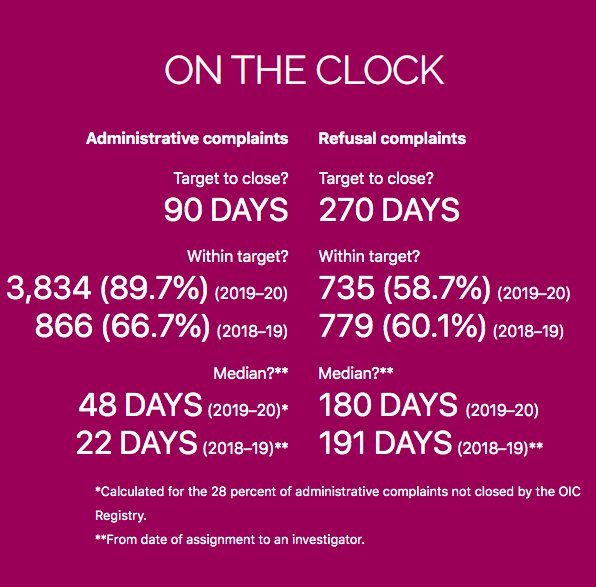

There are plenty of negatives, though. The commissioner’s office has given itself generous deadlines for completing investigations: nine months, for example, to complete a probe into the refusal to release records. About two of every five such complaint files exceed even that target deadline. (I’m citing figures from 2019-2020, before COVID-19 disrupted normal practices.)

And the clock doesn’t start until your file is assigned to an investigator, which itself can take many months. One of my own complaints, made in 2014, was not assigned to an investigator until 2021 – yes, that’s seven years just to start the probe. (The commissioner abandoned the first come, first served principle in 2008.) The commissioner can also decline to accept a complaint if she deems it “trivial, frivolous or vexatious or … made in bad faith,” though so far has never done so.

Some complaint files can take a decade or more to resolve. Under the law, a requestor cannot go directly to Federal Court for a review, but must wait until the information commissioner has completed her own review. That rule effectively holds some complainants hostage, unable to take legal action while the commissioner’s investigation is stuck in limbo.

Complainants are often put in the impossible position of arguing from blank pages. Without knowing the exact content being withheld, how does one mount an argument that the missing information should not have fallen under this or that exemption? Sometimes, the specific exemption invoked is not even noted on the blank page. The government encourages departments to cite exemptions directly on the page of redactions (Citation of Exemptions), but there is no legal obligation to do so. An institution can simply list exemptions on a separate sheet of correspondence. In such cases, it’s not possible to connect-the-dots to the redacted pages to know why information was withheld.

Also maddening is the ability of institutions undergoing complaint investigations to add new exemptions that were never previously invoked. (This practice has been endorsed by the Federal Court.) Call it exemption shopping, or a secrecy insurance policy, or a redaction pile-on, or whatever – it’s a reminder that government’s thumb is on the scale. Indeed, institutions can add exemptions even after the commissioner has concluded an investigation, through their ability to challenge her orders in Federal Court and start the review process afresh.

Finally, cabinet records are excluded from coverage by the Access to Information Act for 20 years after their creation. Requestors rightly suspect that governments routinely abuse this ironclad protection by expanding the definition of cabinet documents, especially given that the information commissioner cannot independently verify the claim by examining the records. She can ask a department to review a decision. Or she can request a certification from Privy Council attesting to the cabinet status of a withheld document. Both approaches are based solely on trust of a government institution.

A problematic complaints process is better than none at all. But fixing the Access to Information Act is not just about expanding coverage and toughening deadlines. It’s also about a creating grievance regime that can effectively challenge institutions that – inevitably – abuse the law.

March 3, 2022